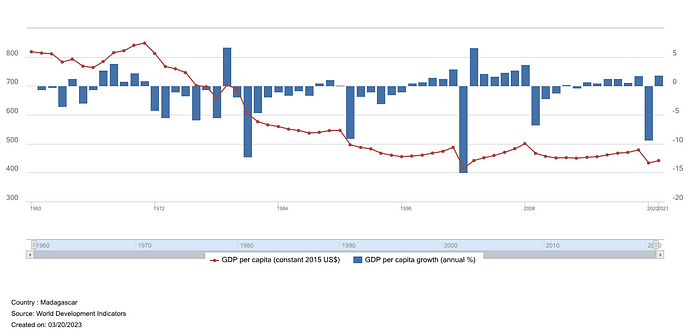

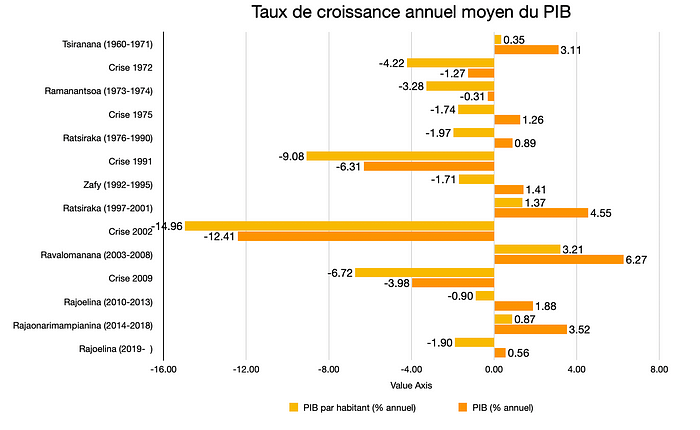

It has been shown time and again that Madagascar is able to achieve high rates of economic growth. The problem seems to be the failure to keep such rates for a long period of time. The occurrence when, just as the economy is about to take off, a political crisis happens has been a constant and persistent headache to policy analysts in Madagascar. Indeed, all past episodes of rapid growth in Madagascar have been short-lived and never sustained. Invariably, those growth spurts were stopped by a political turmoil, each time sending the economy in a tailspin. As a result, policymakers have not been able to reverse Madagascar’s long-term economic decline.

While the cycle of recurrent crises has been well documented, its mechanisms and its drivers have unfortunately not been fully understood. This note attempts to provide a simple narrative explaining how an episode of rapid economic growth is often reversed by a violent political crisis. It demonstrates how economic growth can generate political turmoils.

At the beginning of the narrative, usually in the aftermath of the crisis, we have a relatively peaceful environment. A new governing group is in power. The opposition, weakened by a recent crisis/election or in a show of goodwill, is discreet and quiet. After a period of learning-by-doing, the new ruling class manages to produce a few economic results. The economy shows signs of an impending take-off. Most macroeconomic indicators start to improve and some parts of the society experience clear upswings. Unfortunately, others — some regions, some sectors, some business interests, … — are left out and do not partake in the economic amelioration.

In the growing parts of the economy, new economic elites emerge. They are usually some opportunist members of the new political ruling class. Given that they are not certain about how long they will be governing, they have a tendency to consolidate their political powers. In doing so, they “forget” and fail to implement the much needed checks and balances institutions.

The absence of such institutions would be an implicit invitation to diverse abuses by the ruling elite. Cognizant that their tenure may only be short lived and that they are not going to last at the helm for ever, they will be driven by predatory incentives to extract as much as they can, and as fast as they can, while they can. The resulting rent seeking behavior leads to a very rapid wealth accumulation by very few people, often at the expense of a large majority.

As those “nouveaux riches” flaunt their newly acquired wealth, their winner-takes-and-keeps-all attitude creates envy and frustration among the excluded and marginalized group which will invariably include a set of opportunistc disgruntled politicians (new or from previous turmoil). And with this frustration grow resentment and a sentiment of unfairness which prompt the latters to become more vocal in claiming their share or their place at the feeding table. This, in turn, provides an excuse to energize and galvanize the legitimacy of the weakened political opposition.

Given the centralization of political powers and the lack of proper checks and balances, the opposition has few options but to resort to extra-constitutional methods or to take to the street for their voices to be heard in face of the abuses and excesses perpetrated by the current elite. It won’t be long before a new political crisis start.

The rest is well known — each time the economy seems poised to take off, political unrest erupts! It would be tempting at this point to suggest some straight forward ways out of this cycle. However, while the narrative explaining the phenomenon is by design simplistic and linear, the issues that are dealt with are multidimensional and complex. To attempt to offer a number of prescriptive solutions to this problem would be naive and is beyond the scope of this short write-up.